Demonising the Other

I think it would be true to say that our response to the other-than-human, specifically animals, is schizoid; in fact, schizoid three ways. There are the animals we love, the animals we eat, and the animals we see as enemies.

Our response to our pets is one thing: mostly, we adore them, spoil them, think they’re cute. If they are omnivores like dogs, or carnivores like cats, most of us don’t think about the provenance of their food (even if, as happens in some countries and for export, it includes the bodies of other dogs and cats, still containing the euthanising drugs). (Sorry to start your week on a bum note.)

Animals we keep as prey for ourselves have a much harder time of it. They are as sentient as our pets, as or more intelligent, sensitive to a range of emotions, capable of relationships, whether with others of their own species, or with other species, including us. Their lives tend to be ‘nasty, brutish and short’. We don’t associate the lump of flesh in the oven or on our plates with the living animal, on the whole.

And then there are the creatures whom we hate, fear and demonise – mostly because we don’t know enough about them, but we know they’re inconvenient to our ‘project’, they get in the way. The snail we stamp on. The pesticides we employ to kill insects (including bees, and other pollinators). The shot crows the farmer hangs up to dissuade other crows. The foxes, hunted for ‘sport’. The badgers gassed or beaten to death because we believe – wrongly – that they impart bovine tuberculosis to our cattle (it’s mostly the other way round).

And then there are all the other ‘inconveniences’.

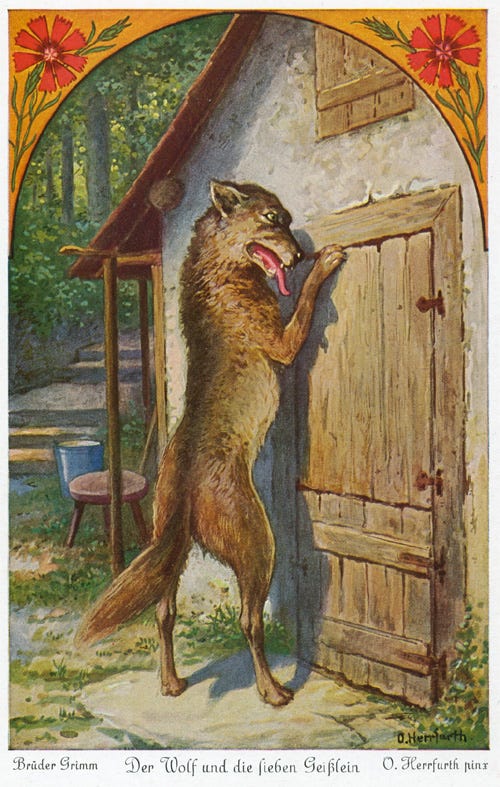

The return of the wolf

Wolves hung on in France for a little longer than they did in GB. As in Britain, however, they were seriously persecuted; and often, en route to a savage death, tortured in bizarre and sadistic ways.

‘Wolf hunting in France was first institutionalized by Charlemagne between 800–813, when he established the louveterie, a special corps of wolf hunters. The louveterie was abolished after the French Revolution in 1789, but was re-established in 1814. At the end of the 18th century, there were between 10 and 20,000 wolves in France based on estimates that showed an average of 6000 wolves killed annually. They would have been present everywhere from the coastal regions to the mountains.

‘Following an organised and sustained persecution, often by poisoning, they were finally completely eradicated from France in the 1930’s.’ (http://www.planetepassion.eu/MAMMALS-IN-FRANCE/Wolf-in-France.html)

It should be said immediately that wolves very rarely kill, or even attack, humans. That is not to say never, but there are more deaths of humans at the fangs of domestic dogs than those of wolves. Wolves naturally fear us, and unless they’re sick or rabid or maybe starving will absent themselves very quickly.

Yes, they do kill sheep. (So, of course, do we – on a vast scale.) But given that we’ve deprived wolves of habitat, and of their natural prey – only 4%, globally, of mammals are wild/free living now – and given that sheep are captive, it’s not surprising.

I realise this is controversial. If you only have a few sheep, you will know them as individuals. If you are a commercial enterprise, then in Britain anyway sheep do not make a profit for the farmer, but they are subsidised. And, of course, many sheep deaths are actually caused by dogs. There are also measures in place in France to help farmers protect their animals from wolves.

Here, the wolf has legal protection, although this has recently been downgraded, and some culling happens. Estimates of how many wolves are in France currently vary from 1000 downwards to 500+ since this culling has been approved.

Over the last 30 or 40 years France has been being naturally recolonised by wolves from Italy. Within a wolf family, dispersal of young males happens. In search of his own territory, a wolf can travel up to 800 kms from the pack.

I’m delighted to report that since 2022 there have been 7 arrivals of young males in Brittany, with 3, currently, ‘in residence’.

Because we can’t stand the wild within, we also can’t stand it without – and of course vice versa.

Your inner rat

A decade or two ago, I was teaching a week of poetry workshops in Sussex, in a spiritual context and on a biodynamic farm.

One morning, there was a ripple of hysteria from the course participants. A rat had been seen a few hundred yards away, in the compost heap.

And? It’s said that we are never further than a yard/metre away from a rat. OK, they can, it’s true, carry diseases. Some rats, some disease. A rat in the compost heap does not automatically mean one is going to succumb to bubonic plague. And on the whole, which is more dangerous to the planet and other species, rats or humans?

So I had them writing about their inner rats, once the worst of the furore (‘We’ve got to kill it!’) had died down.

I see the ‘inner rat’ in this context as being all the dark parts of ourselves we don’t like, we fear, we repress, we project onto others. The best thing we can do for the project of consciousness, arguably the ‘reason’ for being here, is to reclaim all this shit, our own shit. (‘When an inner situation is not made conscious it appears outside as fate,’ said C G Jung.)

Seems it was a helpful exercise.

How to love hornets

It’s hornet season, and a queen has been trying to get in through the bathroom window. I’ve discouraged her – we don’t actually want a nest in the house.

In Devon, the house that TM built was the renovation of a ruined stone barn. In true Devon barn fashion, it has two round piers, one immediately either side of the front door.

One year, European hornets built a nest on top of one pier. TM’s immediate response was that we needed to kill them. I wanted to see what might happen.

What happened was that the hornets spent weeks clearing my little veg and herb garden, and the willow tree at the edge of the courtyard, of blackfly and aphids. What also happened was that all summer no one was stung (European hornets are less aggressive than wasps, or even bees), apart from our friend Francis when, unbeknown to him, a hornet had got trapped in their bedroom and Francis had closed his hand on it when drawing the curtains.

Later that same summer, I came across a drowsy hornet on our bedroom floor. I watched as it tilted its articulated head and scanned my whole body slowly, from my feet up to my eyes – and gazed at me, vulnerable like any other wounded or dying creature, presumably fearing being trodden upon. I picked it up on a piece of card and deposited it in the Virginia creeper out of the window.

(I know they kill bees. No-one is perfect.)

I learned, then, to look, watch, really observe those creatures who might be a threat; and of course at least to try kindness first.

As always, my friends, thank you for reading.

Loved this one

What a very important letter Roselle, apologies for the delay in reading... I am snowed under and will be until end of term, much as I wish otherwise.

I am a great believer in letting things be... wolf - lets call that wolf a wild boar who is persecuted by hunters daily from September 1 onwards, a wolf it would be no different. Rat, we have aplenty in the chicken run... they tidy up all that the chickens leave and hornet, as you say, they are not aggressive creatures, ultimately ignorable despite a hefty sting. Sadly my husband is of the leap up, grab a rolled magazine, kill it quick variety - he would be hilarious to watch were it not for the final action.

And, I am so relieved to read, "The badgers gassed or beaten to death because we believe – wrongly – that they impart bovine tuberculosis to our cattle (it’s mostly the other way round)." I have been trying to explain this to the three landowners here for the last fifteen years... and still the leave bate or traps. I sabotage what I can but I cannot check all three setts on the hill every day... much as I would like to.

I hope your long weekend has been as warm as ours? xx