Once upon a time…

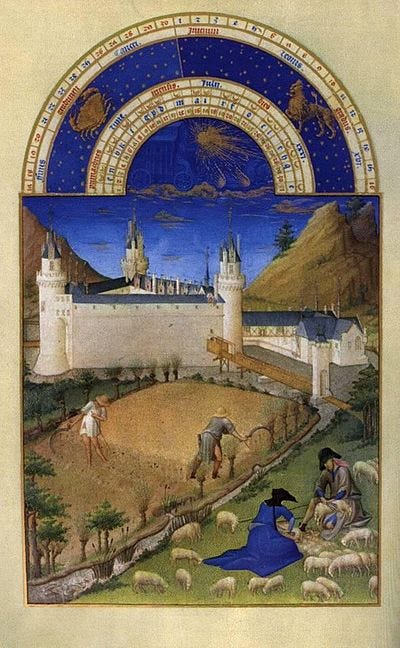

Picture this… there is a cluster of brown hens choockling away to themselves under the apple trees. There is a gentle, slow, heavy horse with hairy fetlocks – perhaps a Breton working horse, a cross between a cob and a Shire, if that means anything to you – gazing over the ancient multi-species hedge of its small paddock to where a rosy-cheeked old woman is giving some vegetable peelings to her pig in its shed, and barley to a milk-cow prior to bringing the latter into the barn to milk her. Adjacent, her husband is shaping a new wooden handle to his digging hoe. A bit further over in the barn, last year’s apples have fermented into cider.

There are two children, her beloved grandchildren, a boy and a girl, playing near the pond with the ducks. The sheepdog is lying in the shade, watching over them. Their parents are occupied with bringing in the first hay harvest, which means here scything a small field, the size of field where if you chucked a stray stone out of the middle it would reach the bank with the hedge on it with no effort, then stooking the hay upright on a couple of old cartwheels.

It’s early, early summer, and dry. Small apples are forming after the blossom. The hedges and meadows are full of wildflowers.

Behind these gently industrious scenes, the house is a typical Breton longère: stone, a beautifully-dressed granite arched doorway, blue paintwork to the windows and doors.

This is a bocage landscape: typical of rural France until maybe 50, maybe 75, years ago. Typical also of the UK, and many other European countries. Small scale, human scale, fields with banks and hedges; plenty of trees; mixed pasture and woodland.

To an onlooker this is an idyll.

Have a look at this link. The painter Lucien Pouëdras, born in Brittany but living in Paris, has made it his life’s work to record, as witness, these scenes of rural life which have been so completely overturned in the second half of the twentieth century; to offset, he declares, the ugliness of our industrialised world, our industrialised agriculture. This is indeed how it was, albeit that Pouëdras’ paintings are also romanticised in content and naïve in style.

Many people, perhaps especially urban dwellers, and most children (quite consciously fed such images by the meat-and-dairy industry), when they imagine country life, picture something similar to this. Or want to, anyway.

However, note that even in this once-upon-a-time, all is not necessarily the Garden of Eden: the family pig is destined only for the chop, as are the chickens eventually. Also note in the cover image of Pouëdras’ painting those rabbits (as far as we can tell they’re rabbits), in the hutches? For eating.

Up in arms (or at least in tractors)

If you’d driven down to Quimper last week, you’d have seen old tyres as roadblocks, rubbish piled and set alight on roundabouts, trees on other roundabouts beheaded at about a metre off the ground. At the weekend, if you’d been on one of the N roads (equivalent of the UK’s A roads) you’d have been at a standstill as convoys of tractors took over the lanes.

If you’d driven east from here the other day, you’d have seen what at first glance would appear to be bodies suspended from motorway bridges (they are in fact the ubiquitous blue farmers’ boilersuits, stuffed). The sight would give you a momentary punch to the gut. And it seems that here in rural Brittany, as in rural Devon where we used to live, there’s a higher than average suicide rate amongst farmers. Farming is very far from an easy way to make a living: barely a way to make a living at all. In France, as recently as 2015, 30% of farmers made €3,500 per year.

My first encounter, many years ago, with such protests was a blockade of cauliflowers spilling over one of the usually-pretty roundabouts and flooding the traffic lanes heading north to the ferry port of Roscoff. At the time, I probably smiled at the Gallic temperament, not realising the import of such a gesture.

Bretons are strong-minded Celts, and Celts, perfectly peaceable if left alone, are good at rebelling if it’s needed. Think Asterix, and that little encampment of Gauls in what was probably northwest Finistère, holding off the Romans. For a long time, the historical inhabitants of this peninsula fought to stay independent of French rule. Later on, think the Bonnets Rouges protesting fiercely against the taxes and the timber that Louis XIV wanted to raise from Brittany to swell his coffers, his navy and the wars he was waging. Think that tiny village of Trédudon le Moine in the Monts d’Arrée here in Finistère, which was honoured as being one of the very ‘foremost pockets of resistance’ in the whole of France during World War II.

So it’s not the first time the rural people have been showing their disapproval; and of course it’s not simply here in Brittany: in fact it started in the south.

Last week, fishing communities joined in. An equally hard life. Does anyone think of that, the danger, the cold, the discomfort of those working the trawlers, or the fact that fish too feel pain, as they tuck into their cod cheeks?

The rural way of life

The protests here are about survival: of the paysans/farmers themselves, of farming, of a rural way of life that is barely visible to the urban dweller. (By the way, here the term ‘paysan’ has none of the derogatory resonances that the word ‘peasant’ can have in the UK.)

How many people actually consider where their food is coming from? Who grew it, who harvested it, the way the sun, rain, soil all played their parts? Whether it’s life-giving food, grown in a healthy environment? Whether the soil was tended with care, whether the animals had decent lives and swift deaths?

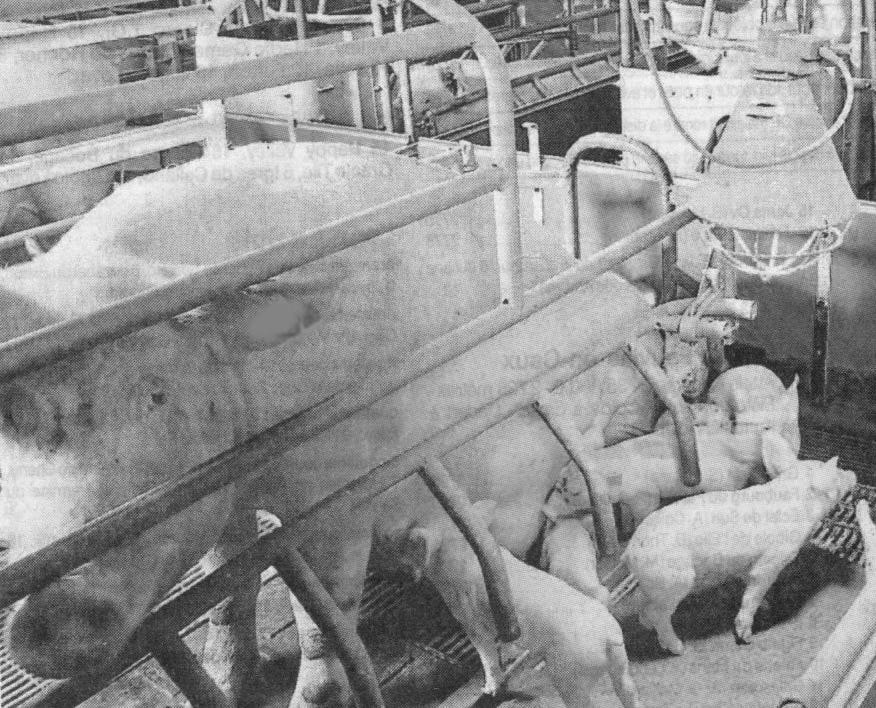

Whether the animals bred for our appetites spent their whole life imprisoned and routinely stuffed with chemicals? Whether they lived, like this sow, in metal cages spending their whole life before their slaughter breeding more piglets for the same future? The only time those animals, highly intelligent and sensitive, by nature made to dig and rootle in fields and woodlands, will breathe fresh air, and see the outdoors, will be on the journey to the slaughterhouse.

The thing is, we have to eat. Food is an utter necessity. When I was a young hippie, I’d sneer rather at the idea that ‘we are what we eat’, thinking that was so pitifully short of what we are: more, much more, than merely a collection of cells. Now, I think differently. Everything in a human being is (also) an effect of what we eat: without food we don’t survive long; plus food not only changes biochemistry but affects mood, thoughts, feelings, energy levels and of course general wellbeing. Food can heal you; or make you seriously ill.

When times are hard, people buy the cheapest. People really are struggling to make ends meet. Capitalism, as my partner and daughter frequently say, inevitably means a race to the bottom. Most people buy their food in supermarkets; it’s rarely organic (often seen as an expensive luxury), frequently imported, and often out of season. Ready-made, perhaps.

The farmers behind our food are are invisible.

An acquaintance said to us once ‘We always cook from scratch.’ TM and I simply looked at them blankly. At that point, we had no idea how relatively few of us there were who did that – to us, home-cooking was and is simply the norm. (Judging by the many celebrity chefs, maybe there is now a resurgence in cooking one’s own food?)

It would make such a difference on a massive scale if people bought local food, at local markets or direct, grown even by people they knew, and bought what was in season; and, of course, organic; and cooked it themselves. (Alert here: I’m currently completing a vegan cookbook, based on the seasonal food we ourselves grow that is also easy to source if you don’t grow your own. Watch this space.)

The curse of multinationals

Supermarkets beat the costs down so that farmers receive pence/cents; one French organic farmer interviewed by the Guardian in relation to the protests said that he was selling his produce as conventional (i.e. chemically-farmed) produce because he couldn’t get the price needed for organic. It’s a truism in the UK that a farmer is paid barely any more – a few pence – for his litre of milk than it costs him to produce it; sometimes not even that. No wonder farmers rely so heavily on subsidies.

‘European farmers have long teetered on a tightrope, struggling with debt, pressurised by big retailers and food giants, hit by a series of droughts and floods, forced to compete with foreign producers and their cheap imports, and dependent on a subsidy system that favours the big players.’ (Le Monde diplomatique)

France is the EU’s biggest agricultural producer, but only 2% of the French workforce is agricultural. This is as a result of two things: one is the vast acreages given over to those relatively few owners, the ‘big players’ who focus on large-scale industrial mechanised agricultural production, mainly of animals and their feed products; the other is the flooding of the market with cheaper imports, despite the fact that there are still thousands of independent producers of meat, dairy, fruit and vegetables and wine here. (The situation with imports in the UK is if anything more dire than in France, but that’s for another post.)

The demonstrators are demanding fairer prices for produce, and for produce in the shops to be largely French, they want subsidised tractor fuel and to preserve diesel tax-breaks for agricultural vehicles, an end to the extra French bureaucracy on top of EU regulations, and and immediate aid for struggling organic farmers. They would like not to have to spend their evenings filling in forms after a day working in the fields or animal units. Who can blame them for that?

But they also want removed pesticides to be reinstated, and are also protesting against set-aside laws: that is, the requirement that they have to leave tiny bits of land for biodiversity. And it’s the system that drives this, rather than the farmers themselves. The current industrial farming system is devouring its own tail, and is either going to completely destroy the planet, or implode.

I have had farming family on both sides, I have farming friends, and have lived among farmers all my life. I know that at certain times of year it’s normal to work 14- or 16-, even 18-, hour days. If you are a farmer with animals, it’s also normal to get out of bed in the dark, every morning, no matter what the weather. It can be a lonely life. It’s always a hard life. It’s almost never well-paid.

I lived on a little peninsula in West Devon that was shut down during the foot-and-mouth crisis of 2001. (This is the backdrop to my novel The Burning Ground.) I heard the stories firsthand; and when we were able to travel again I’d drive the 60-odd miles to see my parents in North Devon and see smoking pyres of cattle carcases in the corners of fields. After that for a couple of years the fields that had always been pastureland were ghostly-empty. Shocking, utterly shocking, to have to kill so many animals, and ghastly for the farmers, many of whom didn’t survive the crisis.

So I sympathise with their disillusionments, their despondency, their despair.

But where are the paysans?

Of course there’s a ‘but’. Smashing trees and burning tyres doesn’t help the environment with which the farmers aim to make their living. Spraying the living daylights out of every passing insect, chemically fertilising the soil, ploughing vast acreages (thus breaking up the topsoil structure and the bacterial and fungal networks) doesn’t tend the soil. In agri-business there’s no sense of land being sacred, something for which we should be so immensely grateful.

And if you are taken for granted, and your work not valued in a laregly-urban culture, what incentive is there to do things differently?

Truth is, few conventional farmers are actually the mythic ‘guardians of the countryside’ that they are portrayed as. My uncle used to tend his dairy cows at pasture on foot or on horseback. He knew every cow. Where we used to live in Devon, the cows and sheep in the fields in summer were checked infrequently by young guys roaring through the fields on quad bikes, often missing the lone sick sheep by the hedge. It was routine to yell and to thwack the cows hard on the backside with lengths of alkathene pipe each time the animals were moved, as it is here – a farmer nearby us has one extraordinarily lame elderly cow, with a very overgrown curled-up toe, even slower than most cows as she is clearly in pain, whom he thwacks hard all the way down the lane to the teetering dirty milking ‘parlour’.

And Brittany has a vast concentration of intensive pig, cattle including veal calves, and poultry units, and very few animals ever out on the field. (The main inhabitants of the fields are the maize crops, as below, to feed the indoor population of animals.) I had no idea how many; and word is that between 1000 and 2500 new intensive farms are expected to be set up in Brittany each year. As this happens, hundreds of smaller farmers are going out of business, and the sizes of the élevages are increasing.

I find this utterly heartbreaking. Had I known quite how many animals live in such relentless captivity here, would I still have come? – It’s not so different in most of the Western world, after all.

Return to the bocage – a revolution in which we can all take part

A bocage landscape is what I describe at the beginning, and what Lucien Pouëdras is painting. As I said, small fields, hedgerows and woodland, crops, vegetables and fruit grown and traditionally harvested by hand or with hand-tools. The photo above is of a small ‘hoe garden’ farm which is a really good example of such earth-friendly farming practices. I recommend clicking on the link.

There may be some livestock; in my vision, there are very few animals kept for meat or other exploitation, many more wild creatures, and a largely vegan planet-friendly diet.

The thing is, growing food is not a hobby or a luxury. Food security is very much already a pressing concern. We cannot, simply cannot, feed the humans of the world on our current diet of meat and dairy, let alone leave space for a healthy population of wild creatures, or forests. Apart from any other issues around cruelty, massive environmental pollution and degradation, water stress, land use, and the resulting climate change – all associated with industrial animal agriculture – we simply cannot afford the vast over-population of farmed species to satisfy our appetites. Animal agriculture, no matter how it’s undertaken, requires a lot more land than growing vegetables.

We worry, quite rightly, about human over-population, but here are some shocking stats: humans make up 34% of ‘mammal biomass’ on the planet. Almost double that is the population of farmed mammals, entirely one way or another to feed us and/or our pets: 62%. I’ve said before that only 4% of the world’s mammals are wild and free-living.

Current farming practices under agri-business are globally as polluting as the whole planetary transport system in total.

Now of all times – before it’s too late – is the time to restore the bocage lands with small-scale peasant farming.

Food is not a luxury and growing it not a hobby: the new peasant

In France, a ‘paysan’ is most commonly used to mean a small-scale farmer, and there is a little revolution happening in rural parts of France, and here in Brittany, of young people pursuing what in the 70s we’d have called a ‘back to the land’ movement.

Until relatively recently, Finistère was very much a peasant culture. We need to return to this worldwide.

Miraculous Abundance, the book I’ve mentioned a few times as a major inspiration for us, puts this well:

‘… the farmers of tomorrow will not come from the agricultural class that has been reduced to near extinction; they will come from cities, offices, shops, factories, and more. One thing is certain, they will not return to the earth using conventional models from the recent past. We need to invent new ways of being farmers in the twenty-first century. The farmers of tomorrow will be the guardians of life. Their farms will be places of healing, of beauty, and of harmony.’

What we need is for people to start growing their own food again, alone and collectively. We need small-scale farms, and we need them to grow mainly plants, as livestock for our consumption need far more land (and water, and soy and maize, and the processing and fossil-fuel transportation of such goods) to produce 1 kilo of protein than plants. We could grow all that was needed for our current population and allow rewilding and biodiversity if we changed our diet.

And what a peasant’s revolution it would be, to take back the power of producing our own food once again. In our own back gardens, on roofs, on balconies, in tiny backyards, on wasteland and common ground, in parks. Dig up that lawn; plant up those small borders with veg. Tiny space? Grow vertically, in pots. Don’t rely on supermarkets. Be autonomous, believe in the vision, share with your neighbours.

If you’ve got to the bottom, thank you for reading this. I’d love it if you shared this post.

Really informative and passionate post with so much to think about. Thank you!

Hello! I've enjoyed reading your posts, I'm in the Lot et Garonne. I think it's really important to keep talking and writing, as you are doing, to share ideas and practical means as to how we can all change our lives and thus our shared future in this magical realm. The spiritual connection to nature is really important and it needs reforging as well as the way we grow and who buy our food from.