To all my lovely subscribers, previous and new: apologies for my absence. It’s been for 3 reasons: one, personal health issues; two, far far too much to do with processing our amazing veg-plot glut for now and for the winter (not that I’m complaining! – it’s just been time-consuming); and three, it’s been almost impossible to find any words to share in the face and scale of the atrocities happening in the world at the moment.

Today I’m simply bearing witness to it all, joy and grief both; and sharing some of the tiny notes of hope I find in this wild and biodiverse corner of Brittany.

The Next Revolution

How we long to overthrow

ourselves, transgress boundaries,

borders, races, states

how we long for a language

that is no language at all

but cadences in the tongue

of sparrow, sea, shell, silence –

here, now, trying to make words

sing like birds or violins

like without speaking; and

all the time beyond the window

the peach tree doing its thing

© Roselle Angwin, from All the Missing Names of Love

(a few copies available direct from me)

*

Nature remains

‘After you have exhausted what there is in business, politics, conviviality, love, and so on — have found that none of these finally satisfy, or permanently wear — what remains? Nature remains; to bring out from their torpid recesses, the affinities of a man or woman with the open air, the trees, fields, the changes of seasons — the sun by day and the stars of heaven by night.’ ~ Walt Whitman

‘The earth does not belong to us; we belong to the earth.’

One of the most distressing facts today is our lack of a sense of felt relationship with our kin in the rest of the natural world. In the West, very few children now are brought up to engage with nature. In Patrick Barkham’s article in The Guardian of 9th August, Miles Richardson, professor of nature connectedness, says: ‘Nature [dis]connectedness is now accepted as a key root cause of the environmental crisis. It’s vitally important for our own mental health as well. It unites people and nature’s wellbeing. There’s a need for transformational change if we’re going to change society’s relationship with nature.’

It seems to me, then, that underlying our current ecological crisis is the loss of a sense of relationship, a spiritual connection as well as a felt relationship, both physical and of the heart, to the earth and other species, coupled with an absence of a sense of deep meaning in our culture with its failures of imagination. I believe that part of this is because we increasingly live in a culture of commodification, where everything is seen as a resource. Somehow, we’ve acquired a mindset, possibly since the farming revolution of the Neolithic era, and not helped by the Bible, that everything was put on this earth for our use.

But we are part of, not apart from. What if we saw us all as one big family, a network of kin relationships, remembering too that the other beings on this planet have family connections of their own, rights and reasons too? How differently might we live if we acted on the idea that we don’t live in a hierarchy with humans at the top, but a circle, a sphere, of life where we are all interdependent?

*

The cure for that sense of separation? Well, going outside

… Just for the sky to open you up, to smell the air, and to catch a glimpse of leaf, bird, butterfly, wherever you are. Bringing your whole attention, just for a few minutes. Make a written collection of these ‘bright moments’.

I have been sitting and watching a tiny recently-fledged wren (with a very loud voice) first dust-bathing and then sunbathing, wings outstretched and beak agape. Five minutes of joy, wonder and uplift.

Who wrote ‘Only birds make me believe in God nowadays’? I might not phrase it quite like that but I utterly share the sentiment. For 50 years, I could say that birds, like poetry, have saved my life multiple times.

Obviously, I’m not speaking literally; rather about soothing and inspiring; increasingly, since in our spot, as a result of organic growing, no chemicals on the land we tend, and a vast amount of fauna, insects, habitat and biodiversity, I can also take comfort in the fact that there are birds. Plenty of birds. Small enough comfort, in our world, you’d think; but pleasure still.

What can we do, at times like ours, those of us who are privileged enough as to have sufficient food, shelter, water and an absence of war or displacement, other than pay attention to the small moments, the many positive tiny events that can construct some small counter-narrative to all the horrors, or at least remind us that there is, still, beauty?

Now that mating season over and nearly breeding season too, plus the summer moult, there is much less birdsong. But the birds are still around. In the course of a single hour, I watched at just 2 metres from the house in the heavily-laden peach tree, on some of the branches broken by Storm Ciaran: a family of wrens, perhaps the same family as that of the individual above that I watched; a family of warblers; and 3 woodpeckers, one after the other: a green, a greater spotted and a lesser spotted. The young buzzard, who has been mewing from dawn to dusk, has been taking flying lessons this month, cruising low over the Home Meadow and the house.

*

Young swallows have been gathering on the lines for a fortnight now.

The swifts have already gone. Imagine spending most of your life, and certainly the whole of your first two years, entirely in the air, sleeping on the wing somewhere up towards the stars alternating one half of your brain shutting down, then the other. They have to drink on the wing, and only touch down when mature to nest.

In another life, I’d have loved to study bird migration seriously. Richard Mabey in his inspiring book Nature Cure speaks of a young migrating swift he rescued: ‘I tried to imagine the journey that lay ahead of it, the immense odyssey along a path never flown before, across chronic war-zones and banks of Mediterranean gunmen, through precipitous changes of weather and landscape. Its parents and siblings had almost certainly left already. It would be flying the 6,000 miles [to South Africa] entirely on its own, on a course mapped out – or at least sketched out –deep in its central nervous system. Every one of its senses would be helping to guide it, checking its progress against genetic memories, generating who knows what astonishing experiences of consciousness… [maybe] picking up subtle changes in airborne particles… riding a magnetic trail detected by iron-rich cells in its forebrain… using as navigation aids, landmarks whose shapes fitted templates in its genetic memories, and the sun too, and, on clear nights, the big constellations…’

Astonishing. Thinking about this miracle lifts my heart.

*

The amazing abundance

And there are many bright moments. Our work here, to feed ourselves, on our smallholding occupies perhaps 4% or 5% of the land we tend with the veg plot, the orchards and the embryonic forest garden. The veg plot, reclaimed and added to, is about the size of two or two and a half traditional UK allotments; next year, with soft fruit additions and maybe asparagus, it’ll be the size of three. TM has done most of the grind, and all the work of initial digging; after that, we mostly use no-dig methods, mulch, compost and occasional green manures to keep it nutrient rich. It has rewarded us so immensely.

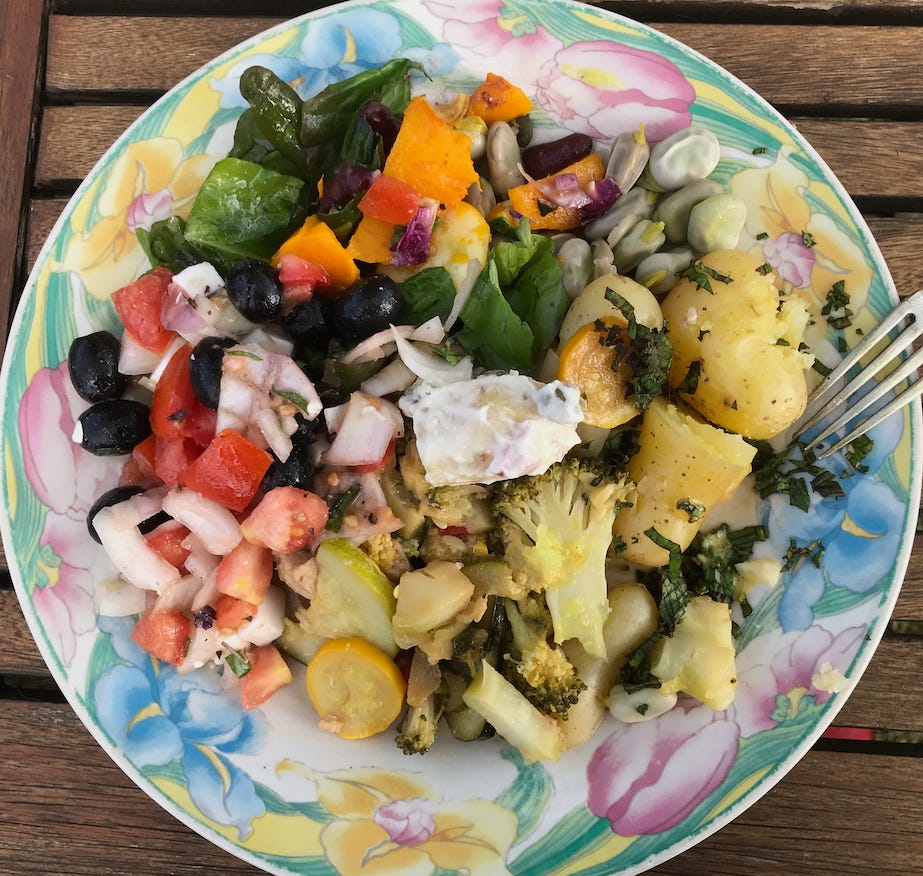

As vegans (TM eats a little dairy still), for much of the year we eat almost entirely our own crops, including the hundreds of different beans we grow, pod and dry or freeze, for protein. This is hugely satisfying.

We are still working on growing grains to balance our diets, and for the bread which we make: this year’s rye crop has been prolific in ‘leaves’, but very short on grains. (There’s a long story about our – er, adventure – with growing quinoa for protein and its eventual failure; another time.)

Other than that, we are dealing with glut upon glut. I find it hard even to write that, given that we know what is going on in Gaza. And actually starvation is a huge problem worldwide. This is not because there’s not enough food, or couldn’t easily be enough food if the meat industry didn’t use so much land and water, but also because of distribution problems. Then there’s that fact that the Western demand for meat means that 82% of starving children live in countries where beans and grains are shipped off to feed our intensively-farmed livestock.

So a glut – what a so-called ‘first world’ privileged problem to have. We frequently say to each other ‘Too much for just two of us,’ without knowing how to resolve that, short of giving it to daughter, friends and neighbours, which of course we do. It’s unclear whether the local food bank can take fresh food from individuals, and so far we haven’t made it when it’s open to find out. However, when we process it to store for the winter, we also know how easily our systems could fall apart, and then who knows who might need to share it with us?

I love the seasonality of living like this. I love watching, from the bedroom or the kitchen window, eastwards in early spring and then through summer, the way each of the seven sweet chestnut trees individually chooses when to open its leaves, then its flowers, and finally when to display its prickly fruits, according to its own sense of time: a different sequence each year, as with the two silver birches that close the row.

Similarly, I love anticipating in the garden the purple sprouting broccoli, the first broad beans, the new globe artichokes, new potatoes, beetroot, carrot, courgettes (a glut of, for which I’ve now developed about 13 vegan recipes; I’ll post a couple next time), the 40-odd squashes ripening away in the garden, for winter. Already I’ve begun the job of gathering, podding and freezing the first of the beans, the mainstay of our winter protein.

I did love anticipating the tomatoes: we actually invested in a polytunnel after a fair bit of agonising on my part about all the plastic. In my imagination, we were going to carry pillowcases of tomatoes up to the house to freeze for winter. TM with others’ help put it up, weeded the ground, and composted it, I sowed and we planted 40 tomato plants. They, like every other tomato plant I’ve grown in the last 8 years, in Devon or here, got blight. (There’s a postscript to this: one or two, seriously defoliated, look as if they are pulling through.)

*

The problem of meaning

All this does raise the question of what we are actually doing, and whether it has enough meaning. Behind it is the ideology of compassionate low-impact living with minimal exploitation of or harm to any other being or the land. In our minds, this is a trial project on veganic growing and vegan self-sufficiency, completely organic and in harmony and collaboration with the local ecosystems. On a bad day, it’s just too much work merely to provide food for ourselves, we are not even off-grid, AND we still use fossil fuel (though our heating, hot water and cooking in the winter all come from trees that have fallen on ‘our’ land, and our composts, woodchips and other mulches come largely from within our own boundaries too).

I have spent almost all of my working life, in my writing and my facilitation of courses and retreats, focusing on enlarging the scope of our individual inner worlds with self-awareness and imagination, where writing is both exploration and expression (Fire in the Head). This is an aid to wellbeing; an aid to compassion (novelist and poet Lindsay Clarke once said that compassion is not possible without imagination); and a necessity for our relationship with Other, human or other-than. The world needs people who are awake maybe more than it ever has.

About 20 years ago my focus shifted in my writing groups from exploring the transpersonal dimensions of mythology, psychology, and shamanic and Zen practice to enhance our personal awareness, to taking these ideas outdoors, working with groups directly within the domain of the rest of the natural world. (The Wild Ways.)

Initially, we were going to ‘nature’ for healing our wounds and inspiring our writing; and it certainly does that. Now, my question is more to do with ‘what can we do for the rest of the natural world?’

Initially, we were going to ‘nature’ for healing our wounds and inspiring our writing; and it certainly does that. Now, my question is to do with ‘what can we do for the rest of the natural world?’

For me, these inter-relationships with our kin in the more-than-human world, along with hands-on – or really hands-off – facilitating serious biodiversity, increasingly drive my life. Something to do with walking one’s talk; congruence with values.

So here, in our spot, much of the rest of the land is woodland, some established, some regenerating. We mow a little of it, mainly around the house, and for paths in the back field. We have a huge amount of diverse shrubbery with flowers for bees and butterflies and berries for birds through a great deal of the year; old roses, herbs and edible perennials, banks and a pond, all except the edibles minimally tended. This is a happy coincidence of my and our commitment to trees and to wildlife habitat, and lack of time and energy to do more than feed ourselves and maintain some small areas. (As TM says, ‘benign neglect’.)

Every day we see signs of foxes, badgers, pine martens, an occasional red squirrel and, as I’ve said, a great many bird species.

Best of all, we have areas where humans don’t ever go.

Wildlife refuge status

Yesterday we had a visit from the LPO, the French equivalent of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, an organisation whose remit is now much broader, to do with restoration of habitat and biodiversity generally. We have, subject to the paperwork, been given the status of a wildlife refuge. ‘Do we meet all the criteria?’ I asked the representative. ‘Oh and more,’ he responded, ‘including some I hadn’t thought of.’

This makes me inordinately happy. They will also provide us with a barn owl nest (I heard one shrieking very close by – probably in said peach tree – the other night; below us in the kitchen I also heard the dog jolt in his basket at the unexpected screeches). The next morning, up by our meditation bench in the North Field, I found a shed breast feather, tipped in gold, from a barn owl.

He also suggested ways to encourage swallows to nest in one of the barns. I’ve been tremendously upset by the absence of swallows, though at the beginning of the season a pair, newly returned, kept swooping in to check out our sitting room. This must be a kind of race memory: the bit we inhabit was once, and anciently, a stone stable, though it must have been converted at least 30 years ago. Sadly, they didn’t nest in any of the barns; I so hope they found somewhere, with all the barn conversions and renovations; all the doors deliberately closed against them (yes, it happens).

And more good news for us: the North Field hosts many fruit and nut trees that we’ve planted. We’ve an avenue of willow saplings for one-day coppicing. We’ve had to hand-water all the young trees from the rain butts in the Home meadow this year: a big job, and TM has done most of it; but 200 willow saplings are too much. They are having to take their chances.

It’s a large area, and at the Western end is a self-sown spinney of crowded tiny oak saplings dotted with the odd sweet chestnut. Having LPO Refuge status may give us access to European grants for planting more native trees, and we may even have some volunteers. This will all be a bonus, for obvious reasons (lack of money and only 4 hands, though often only 2, in fact, this year, because of my broken foot), but also it will help us feel tied into a network of like minds. And isn’t such a network, on a human level, crucial for true community action, and for our hearts? The older we get, TM and I, the more we appreciate community.

*

Anyway, that’s more than long enough. Thank you for reading. For those of you who signed up because of my writing work, I’ll post something for you soon.

Till then, find some bright moments, and if you write yourself, remember the late John Burnside’s words that making a poem is an act of hope.

PS The dog says ‘Surely liking, commenting on and sharing Roselle’s words is also an act of hope?’ ~ Oh yes; agreed.

Hello dear Pauline - how kind of you. Thank you.

I hope life is being a little more kind to you than when we last 'spoke'? x

Full of admiration – thank you for all you are doing. Lx