Everything is relationship (conscious or not)

We are, of course, never NOT in relationship. We live in a world where everything is, as Buddhism reminds us, utterly interdependent, utterly interconnected. There is so much to say and write about relationship, and I have over many decades; in various of my books, on my websites, and one could say that all of my courses are about relationship, in its many and varied forms – and in my old blog.

We are, of course, never NOT in relationship. We live in a world where everything is, as Buddhism reminds us, utterly interdependent, utterly interconnected.

Here, though, I just want to focus on two aspects. One is that according to various value and belief systems, including my own, the ‘point’ of our journey here on the earth is increased consciousness, which first and foremost applies to how we live in relationship to the whole of the sentient world.

It’s easy to think that our relationships are basically confined to our human relationships, and I certainly don’t want to de-emphasise those: they may be, probably are, our greatest teaching areas where we continuously, if we could but admit it, bump up against our own shadows, in Jungian terminology – the parts of ourselves of which we are not conscious, and which we tend to project on others. Then there is – arguably – our own relationship to our inner lives.

But what about our relationships to the more-than-human world?

And/or to our food…

This post is mainly about this second aspect: food, what we eat and how we source it. Do we simply follow our appetites and buy what’s cheapest (and I know that’s an important consideration), or do we make a point of choosing food that is delicious, healthy, good for the planet and good for others, human and other-than-human both if we possibly can?

Food is both a fundamental that keeps us alive, and a celebration of life. Sourcing, cooking and sharing good food is a political act, as I’ve said before; and an act of revolution in a fast-food culture. I love the fact that in France any food is an excuse for a festival: fête of sweet onion, of chestnuts, of mushrooms, of garlic, of snails, of oysters, of wine or cider of course, of cheese; locally there was until relatively recently a butter festival where there was a real cow being milked and the milk being churned on the spot to make butter; now it’s turned into a bread festival with a community outdoor bread oven where – yes – they make bread on the day. There is even a fête du ventre: a festival of the stomach.

A mindful approach to eating

For many years I attended Zen retreats, conducted at least in part in silence. When you share a meal with others in complete silence, and in a meditative and reflective state, and the meal opens with a reminder of the journey of that food to your plate, the seed watered and warmed by rain and sun, tended by someone, gathered by someone, prepared by someone and brought to your plate, you do start to think more mindfully about just what you’re eating. Somehow gratitude rises to the surface again.

It’s not only how you eat, but where it’s come from, whether or not it has required exploitation of an animal, fish or bird, or a human who’s grown or harvested it; whether or not it’s ‘dead’ food in the sense of processed food lacking vitality; how many food miles it’s needed if out of season; whether or not it’s laden with chemicals and the cost to other species and the environment if so, and so on. (The retreat food is always vegetarian and sometimes vegan fare.)

As you will know if you’ve been reading this blog for a while, here we both spend an inordinate amount of our time on food-growing, one way and another. As I said in a previous post, sometimes we laugh at ourselves that it takes so much of our time and energy when we are both people who love the life of the mind and ideas. But we are trying, like so many of you reading this, no doubt, to live according to our values on this very small planet that can’t easily support 8 billion people without our radically changing our diets.

For us, this solution is veganism, including for the dog (more on that another time). We grow our food in a vegan and closed-loop system where we give back to the land what has grown on the land (for instance, yesterday we spent three hours chipping the beginnings of the hardwood branches that came down in last November’s storms to use as mulch; there are many hours still to go as we have other piles of branches).

Having said that, TM has not given up dairy; and I still find it very hard in this country to source non-animal foods for myself if we ever go out (plus the French cheeses of course are utterly delicious).

Why veganism?

As you might know, I’ve written a whole book on the rationale for veganism, accompanied by many recipes from our potager here. It should, all being well, or ‘normalement’, as they say in France, appear this time next year.

Because I have written many pages on the facts in relation to veganism in that book, and also written a couple of posts on the subject (here and here), I’ll summarise my thoughts here, and attempt to be brief. I do have a lot of references to data in the book, but all of what I say below should be easy to follow up on the web.

In a time when we feel so helpless, many of us, to address our spiralling climate crises, here’s something really positive you can do. (If you feel unprepared, there are many good books on vegan nutrition, one of the most comprehensive of which is Optimum Vegan Nutrition, by Patrick Holford, a top UK nutritionist.)

I turned veggie when I was 16 (a frighteningly long time ago) when I realised I did not want to be part of a culture that caused so much harm. The production of meat and dairy is intrinsically tied up with a great deal of animal suffering. Most meat now comes from youngish animals kept in intensive conditions with no access to grass, fresh air, play, etc, and killed young. There are many documentaries that show that the farming and their treatment is often very far from humane. There must be a fair bit of trauma involved in many aspects of that, including the very crowded conditions, and the fear and distress in transportation and in the air at the abattoir.

For many years I was lacto-veggie: that is, I continued to eat and drink dairy products. When I found out just how inhumane it is, and how costly to the environment, I decided I had to stop, though it took me a while. But consider this: we are the only species that drinks the milk of another mammal, and drinks it as an adult, too. And consider that 50% of all calves that have to be born to keep their mother in milk will be males; they will either be killed at birth or raised indoors for a short life as veal.It is environmentally a great deal more costly to produce meat and dairy. The emissions alone are equal to or even greater than the world’s combined transport systems. There’s a lot to say about this, and about effluent in the rivers and sea, but not here.

Also, we could feed many more people on a lot less land, and leave plenty of room for reforestation and for other species, if we cut out food animals, as animal protein is inefficient to produce. (I’m often told that sheep are the only beings that will survive on bare uplands: well, the uplands are bare partly because of over-grazing, and what about the trees that would otherwise colonise?) Also, the clear-felling that takes place in eg the Amazon to produce soy and corn is as a result of the animal feed needed for intensively-farmed animals that we then eat. (Humans consume directly less than 10% of the world’s soya.)

‘The research showed that vegan diets resulted in 75% less climate-heating emissions, water pollution and land use than diets in which more than 100g of meat a day was eaten. Vegan diets also cut the destruction of wildlife by 66% and water use by 54%, the study found… [plus] even the lowest-impact meat – organic pork – is responsible for eight times more climate damage than the highest-impact plant, oilseed.’ (The Guardian, 20th July 2023, from an Oxford University study.)Human suffering: 82% of the world’s starving children live in countries where the major cash crops are maize and cereals for the intensively-farmed livestock in the affluent West.

Human health: yes, vegans can get enough protein (and calcium and, with care, B12). Many of our top athletes are vegan. And increasingly research is connecting certain types of cancers – bowel, stomach, prostate, breast especially – and heart and digestive issues with high consumption of red meat, especially processed red meat, and dairy. There’s also less incidence of diabetes in vegans.

Then there is antibiotic resistance in human health and medicine, surely at least in part due to the routine prophylactic feeding of non-organic livestock with antibiotics.

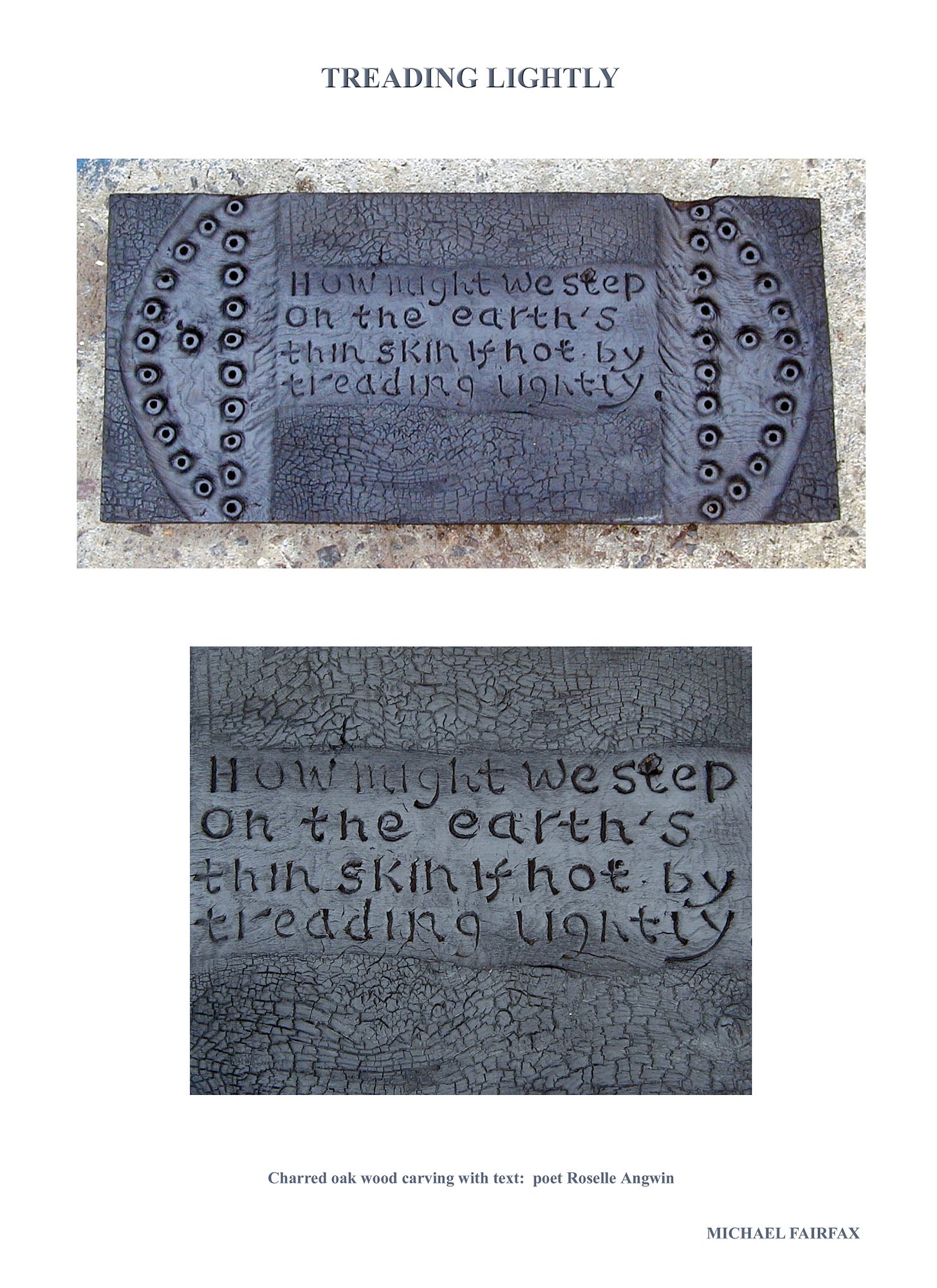

In a minute, I’ll speak more about health, particularly in relation to dairy, and also in relation to my friend and fellow writer Fabienne Bozec.Congruence: for me, as I mentioned, there is an ethical and spiritual dimension to not eating animals, which is to do with attempting to keep my footprint on this earth light, to cause as little harm as possible, and to live according to my values. To live ‘right’.

Oh – and it’s cheaper.

I should say here that I’m not advocating any kind of processed food or meat substitute. I have always cooked almost entirely from scratch using organic wholefoods and fresh vegetables, currently largely from what we grow; there is a great pleasure in that. Trying to eat seasonally and from local food also goes a long way towards minimising our impact on the planet.

Talking of such things, last post I promised you some recipes for chestnuts; I’ve decided to attempt to be more organised, so I will post them later, separately.

Food as medicine

I’ve spoken before how I had a kind of revelation aged 16 which converted me to vegetarianism, introduced me to Zen Buddhism, and showed me a holistic approach to life via my involvement in the counter-culture. This has shaped the whole of my life since: in the way I made/make my living, in my commitment to psychospiritual growth, and my refusal to rely on allopathic medicine, and in what I eat and how I live.

I’ve always used herbal preparations for our family, including the other-than-human members; and I’m proud to say that my daughter never once had antibiotics as she grew up. I see food as medicine, and a healthy organic wholefood and fresh plant diet addresses this. (A very good book on this subject, now old but still relevant, is Nutritional Medicine by two doctors, Stephen Davies and Alan Stewart. Michael van Straten has also written very helpful books with much information on food as medicine.)

There is a school of thought that most illnesses start as inflammation in the body (clearly, from a holistic perspective, the psyche is involved too). Gluten is a big culprit; but dairy even more so. (My vegan cookbook omits both.) For me, eating either food gives me puffy eyes, mouth ulcers and an arthritis flare-up; all inflammation. Common symptoms are eczema, asthma, blocked ears and nose, sinusitis, a red rash across the cheeks and bridge of the nose, digestive issues, weight gain or bloating.

If you suffer from any of the symptoms above, it’s worth trying three weeks without dairy, then have a three-week break. Note how you feel after omitting dairy, and then after adding it back in for the second three-week session. If you don’t feel any difference, try three weeks without gluten (and ditto). 80% of adults don’t have the enzyme, lactase, to digest the lactose in milk; and many people can’t readily digest gluten, as it’s a relatively ‘new’ grain in parts of northern Europe, having only been grown for the last 2000 years or so(!). It seems people from the Celtic uplands do better with rye, oats or barley than normal wheat, as these would have been grown in such places for longer. I do OK with a low-gluten wheat such as einkorn; and I eat a lot of buckwheat.

Especially for women as we age, we are advised to be sure to eat enough dairy for calcium. Ironically, more and more research seems to suggest that dairy milk actually strips calcium from our bones. Vitamin D, magnesium and non-dairy calcium are potentially more useful (I’m not a nutritionist, however, just a food nerd; so don’t take my word for it).

A clue to dietary reactivity or allergy is the food you crave: it’s so often something to which you are sensitive, reactive or allergic. I still crave dairy and ‘ordinary’ bread.

Many diseases can be addressed by looking at the foods that might cause inflammation in your body. The Guardian has just posted an article on inflammation and foodstuffs, if you want to know more.

Healing with a raw food diet

‘Each [of us] is questioned by life; and we can only answer to life by answering for our own life; to life we can only respond by being responsible.’ Viktor Frankl, on how he survived a concentration camp.

We can’t always choose what happens to us, but we do have a choice over how we relate to it, and what we do about it. With insight into this idea of food as medicine, coupled with enough willpower, determination, belief and grace, you can turn your life around.

And so to Fabienne, whom I mentioned above, and who has done just that: transformed her lifelong suffering into strength and energy.

My friend Wendy Mewes gave me such an inspired birthday present: a workshop session with Fabienne on raw food, that is, ‘living food’. I already eat a lot of raw food, but in those two hours I learned so much, as Fabienne’s diet is about 80% vegan raw food. At the end of it, I came away with a few jars of lactofermented vegetables from our garden (rainbow chard stems, sweet potato, red cabbage and beetroot), and a delicious raw apple crumble.

Here’s her story:

‘60 years ago, I arrived on earth with dislocated hips and a crooked pelvis. As a youngster, I was hospitalised more than once, and ended up with screws in my hips and degradation of the joints. 10 years ago, I could no longer walk without crutches, due to osteoarthritis and severe osteoporosis. I was presented with a medical solution: prostheses. It seems that was the only solution.

‘Something clicked that made me review my diet.

‘I am not completely cured because my hips remain damaged, but thanks to living [raw] food, I’ve avoided having to have hip replacements even though I have been promised them for 30 years!’

Needless to say, Fabienne no longer uses crutches.

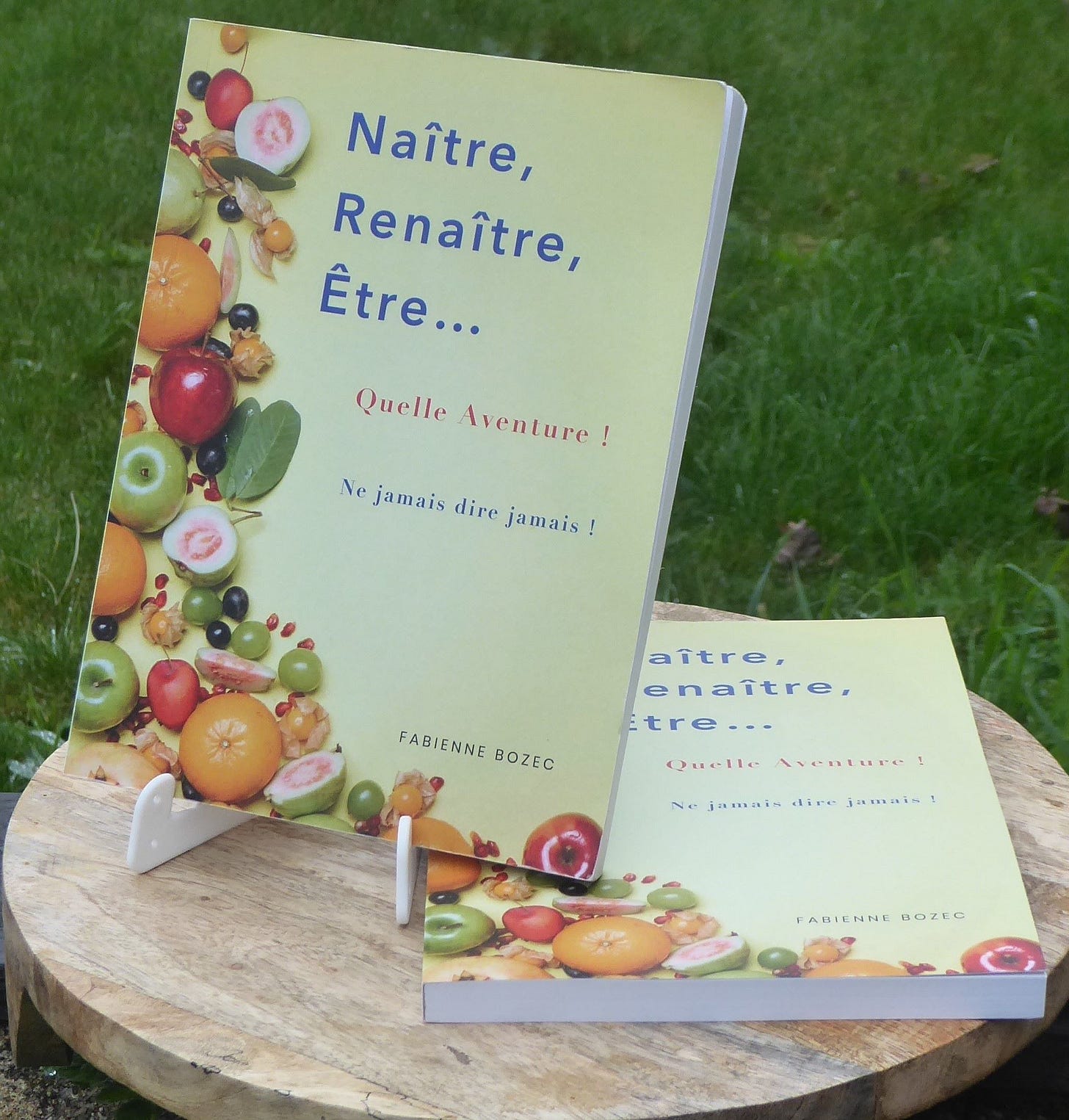

Her book Naître, Renaître, Être is the story of her journey. Despite her health issues she writes lightly. She says of the book: ‘In it I invite you to question the contents of your plate and its impact on our well-being and that of the planet.’

Thank you for reading this. If you found it interesting, I’d love a comment, share or like. If you want more info on any of it, including Fabienne’s book, don’t hesitate to ask.

So many things here. Thank you, Roselle.

I've enjoyed reading you. Thank you so much for the bit about my story and my book.

See you soon